Pugg's Portmanteau Read online

© 2019 D. M. Bryan

University of Calgary Press

2500 University Drive NW

Calgary, Alberta

Canada T2N 1N4

press.ucalgary.ca

This book is available as an ebook. The publisher should be contacted for any use which falls outside the terms of that license.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bryan, D. M., 1964-, author

Pugg’s portmanteau / D.M. Bryan.

(Brave & brilliant series, 2371-7238 ; 9)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77385-050-4 (softcover).—ISBN 978-1-77385-051-1

(PDF).—ISBN 978-1-77385-052-8 (EPUB).—ISBN 978-1-77385-053-5

(Kindle)

I. Title.

PS8603.R887P84 2019 C813’.6 C2018-906351-3

C2018-906352-1

The University of Calgary Press acknowledges the support of the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Media Fund for our publications. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. We acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program.

Editing by Aritha van Herk

Copyediting by Kathryn Simpson

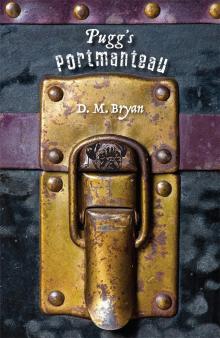

Cover image: Colourbox 20147823, 31383713, and 16008870

Cover design, page design, and typesetting by Melina Cusano

To Richard, Joel, and Aphra

Chapter 1

Pugg’s Note, the First.

Today’s weather drizzles and drops grey threads. Outside hangs like an engraved page, steely with strokes. Rain falls upon flagstones where puddles ink and flow. Inside, the tile floor of our building is dry but wintry enough to feel damp. I paw at your feet, having brought you a grimy leather portmanteau: a case round at each end and cylindrical in between. Three well-creased straps with tarnished brass buckles secure its curving lid, fastened tightly in the manner of a fist furled. The case has a well-chewed handle on the top, and this gives me the purchase I need to drag it to your feet. Now I waggle my tail from side to side and set my head at an obliging angle. I bark, once.

Your expression mirrors mine, both foreheads folding into puzzle pieces. You bend down to the portmanteau and undo the buckles. The case does not belong to you, and I worry you might scruple to open a stranger’s possession, but no, without hesitation, you fold back the weather-beaten lid and expose the contents—a bundle of ragged pages, now mine, although I’ve made the least part of what’s contained therein. You take up the top sheet and read: Today’s weather drizzles and drops grey threads. You wonder what you hold in your hands, and well you might.

Dear reader, stay with me and I will compound marvel with marvel. You see before you an elderly pug, but in truth I am older even than I seem. When you and I first met, I was already ancient by the reckoning of animals and men alike. For more than two hundred and fifty years, I’ve led a dog’s life here in London’s courts and thoroughfares, and this city and I have aged together. I’ve pissed on every model of lamppost ever designed for its wandering streets. I’ve watched as link-lit lanes gave way to hissing lamplight and sewers were dug to flush away ordure and odour. I’ve dodged coaches, chairs, hansoms, horse-drawn trams, steam trains, bicycles, and motorcars. One moment, I was biting at the heels of the fife-piping grenadiers, and the next, I cowered as Doodlebugs buzzed a blitz-dark sky. Cobblestones vanished and cement spewed, curing in tough squares. Commons grew uncommon. Chickens, pigs, cattle, alpacas, and horses disappeared, until only cats and dogs remain. Until, of all the animals I knew, only I remain. I passed a score of years, two score, three score. My age grew improbable and then impossible. Every decade I changed families, finding myself a new home: a garret in Spitalfields, a terrace in Fulham, a council estate in Willesden, a squat in Shepherd’s Bush, a houseboat on the Thames, a flat in Canary Wharf. Now, I live here with you, tucked into a white box, stored in a black tower. We live more in the cloud than on any street I recognize. And now I, Pugg—the dog who seemed ready to outlive London—catch myself at last in the act of dying.

Beginning to die changes a dog. You too, reader and master, have seen the signs: grey hairs at my muzzle, stiff hind legs, damp evidence of occasional incontinence. All kindness, you clean up after me and call me “puppy” when you ruffle the fur around my neck, but we both recognize the meaning of that extra gentleness in your fingers. You know. I know. My impending death surprises you not at all, but it astonishes me—old as I am, I have never yet died. And yet, death comes.

Yesterday a deliveryman came to the flat, his face on the picture-panel beside your door. You pressed the button that allowed him entrance and he rode up in the elevator, finding us by our number, not by a signpost, no Golden Head to mark our door. Without a footman to provide the service, you yourself opened that featureless wooden slab. The liveried—nay, uniformed—deliveryman stood in the passage with your parcel in his hand. “You’re a great one for the reading,” he said, passing over the package, a book-shaped cardboard oblong. The whole time, I could see him looking between you and the shelves that fill our flat, and before he turned away, he spoke again. “Dying art—books,” he said, and then he left us standing there, neither of us with a word to say in reply.

Dying art. Dying dog. More than an accident of timing gives my anecdote its bite, for in that moment of shared silence I understood the finality awaiting me, and I knew the time had come to dig this worn portmanteau from its hiding place. I keep it near me always, and so I have become adept at finding those situations where a manky leather case need not explain itself. And today, my reader and master, while you imagined me footling overlong behind the planters on the terrace, I ran faster and lugged harder than I have in years. I fetched my treasure and dragged it to your feet. Now you have touched its mottled skin, opened its buckling cover, and rustled its papery core. You look up from this page, straight into my brown eyes, and I return your gaze. There is a question in your look: what do you hold in your hands?

What indeed. A thick sheaf of papers, of which these are only the uppermost, wrapped in a protective shell of leather—my portmanteau. Bulging, blotched, and reeking of years, the case is unprepossessing, even ugly. But if you would see it as I do, imagine fine boards covered in goatskin, with marbled endpapers and uncut pages. Imagine a volume so handsome you yearn to take it between your palms. Use your knife to part the first fold of creamy paper, laying bare the houndstooth pattern of type. Bury your nose to smell ink and paper, traces of linen and soot. This is what you hold in your hands. A book in the shape of a portmanteau. A testament to a dying dog’s wish that you keep reading.

Stay with me, and I will tell you how I became the portmanteau’s keeper, long ago when its leather still showed amber smooth. Reader, follow me back to 26 October 1764, to a certain house in Leicester Fields. Press past the footman, up the stairs, and into the best bedchamber. Do you see me there, a much younger pug, shivering beneath the squat protection of an armed chair? Once you have fixed that picture in your mind, reader, print around the edges a heavy black border, a funereal frame, for lying dead upon the disordered linens was my first and best, my dearly beloved Master—William Hogarth, painter, printmaker, paper-seller extraordinaire.

I was half mad with grief, growling and yipping beneath my chair. Faithful cousin Mary Lewis, just risen from her vigil in that same seat, now stood hard by, her face buried in green bed-curtains. From the depths of those stiff folds came the cries common to all creatures, guttural pleas to the eldest power. She’d done her utmost, writing to Jane, still in Chiswick, but the letter sat on a table nearby, awaiting morning and the post. Underneath that impotent missive lay

a sheet of paper, part of my Master’s correspondence with a printer in Philadelphia. Full of a good dinner and with a steady hand, Master Hogarth had drafted its contents, innocent of the future. Then he went to bed. Almost at once, he rose up again to ring the bell so hard he shook loose the clapper. Then followed the vomiting, the crying out at the light, the pain.

Two hours he keened and kicked. Once Mary put me on his lap, hoping to distract him from his distress, but when he looked at me I saw how one eye drooped, his features done in wet paint. He called me by all my names—Pugg, Trump—and other titles that never were mine. A moment later he could call me nothing, sinking back into the bedclothes, a pale, sweating white, all line and tone wiped from his surface. Then Mary made noises, and I smelt only death.

A brown fug, perceptible to my keen dog’s nose, rose from the body on the bed. I barked, flattening my ears and showing my teeth in a grin of distress, but to no avail. The fug grew thicker and moister, pervading the close atmosphere of the bedchamber. I began to pant, swallowing the air in quick puggish gulps, and I made my decision. I intended to lie down, there beneath the chair’s stout legs, and move no more. Faced with my Master’s death, I myself meant to die.

Beneath the bed I crawled, all fat legs and claws scrabbling sideways. A resurgent smell, at once salty and inky, pulled me there—my Master’s scent, stubbornly returning. I sniffed and sniffed again, tracing the scent to a strip of red-brown hide, tanned and gleaming. Grief has its own logic, and a wise dog knows not to question it. My teeth closed on the handle, and so deeply did I bite the leather, my tooth marks still show to this day. I tugged and tugged, emerging from beneath the bed with a large, leather portmanteau. Dimly, I heard Mary Lewis call my name, but she would not leave that empty husk that had been my Master, and neither did she part me from this new object of my attention. Growling in the back of my throat, I backed from the room, holding tight between my teeth the leather so sweetly spiced with his aroma and my redemption.

Downstairs I went, tugging and pulling all the way. I towed the portmanteau as far as the rug in the front parlour. No lamp burned in that room, but by the feeble glow of the window, I looked at this odd leather case. I clawed at the object to better understand what it was. With my nose, I pushed it upright, but it fell over. Then, the cover flapped open of its own accord, and papers and prints spilled onto the carpet. I crawled upon those pages and dropped to my belly, grunting to myself in my puggish voice. Around me the house huddled, stilled and shocked.

I saw dark marks upon the spilled pages, forming into pictures pleasing to a faithful dog—it was my Master’s work, I knew. A moon in eclipse. A ruined habitation. An orb on fire. Between my paws, a tower threw itself down, sending bricks and timbers tumbling. A paper burned, a skull grinned, and an artist’s palette split apart. Images of the end of time and a comfort to a dog in my state of mind.

Long I lay in the dark, panting over my treasure and mourning the man-shaped hollow in the room over my head. I remembered how his deft fingers first lifted me from my littermates, and I felt ashamed to recall how I contracted like a muscle in his hand, sinking my puggish teeth deep into his thumb. In that moment my Master showed his mettle. Where a lesser man might have yelped in pain, flinging me hard against the wall, my Master only laughed and shook his hand free, calling me pugnacious, a fighter like himself. To his human companions he showed off the red print of my teeth in his thumb’s skin. He called me his apprentice and the jagged bite my indenture—that division in the paper contracting student to master. Then he took me more firmly in his grip, wrapped me in an ink-stained cloth, and took me home.

From that day on, Master Hogarth kept me well, restraining me from my passion for the street, where horses’ hooves and rolling wheels endangered not just my paws and my tail but my whole life. I ate well, dining on table scraps from his hand, and from the sweet-smelling fingers of the Jane we both loved so well. Exercise I took by my Master’s side, and wherever he went, I followed. I sat beside him when he sketched with inky lines and washes on sheets of rag paper. I stood by his side when he transferred those designs to the copperplates of his trade. By the tweaking odour of ink, I learned the scent of the presses where the plates transferred pitchy lines to buff sheets. Wet and shining reproductions I saw in abundance, each like its neighbour hanging on the drying line. Fine folk came to view the latest in my Master’s print series, to purchase sets of six or eight or twelve images to bind into books or to hang on their walls. Each series told a tale, a modern moral subject—this was the name my Master gave the story-pictures he drew and printed, and which made his name in the world.

Abundant praise the gentry gave my Master, and me also, stroking us and admiring our pluck. Behind our backs they noted our resemblance, our short, upturned noses, our round, curious eyes. When my dog’s ears caught such whispers, I lifted my chin as much as a pug can, and I trotted more proudly at my Master’s side. I would have doggedly followed him to the afterworld itself, but alas, he passed over the threshold without me. He left me to lie alone on the parlour floor, listening as feet passed, treading upstairs and down.

No one thought to search out a dog. I put my head on my paws and did not know I slept, but when I next raised my snout the window flushed a little, turning a traitorous pink. My Master was dead, but I had light, and I had life, which I did not want then, although I want it now. Distressed, I pushed myself to standing, confused by the printed pages between my close-clipped nails. By the window’s glow, I could attend more fully to the other sheets smeared across the parlour rug, a portmanteau’s worth of paper. On a nearby page, pale and oblong, I noticed dark marks. Excited, I nosed at the paper, pulling it toward me until I could make out the claw marks of printed words, and then without entirely intending to do so, I began to read.

Indeed, the task is not so difficult as it might seem. Consider how the world is already full of wonders: cellular division, exploding stars, acts of selfless assistance. Compared to these, a literate dog is a modest matter. Truth be told, I’ve borrowed many a book from your bookshelves, taking down volumes with my teeth, turning pages with the tip of my tongue. I have as much curiosity as anybody, and learning to read was the best way to scratch that itch. At first, I only gnawed at books as innocently as any infant scholar, but I did not long remain so artless. Soon I learned to settle my paws on either side of the covers, sniffing at the marks that raced across the page. With application, I began to recognize letters, which in turn clustered into words, each attached to an important idea like “sausage” and “beefsteak.” With experience, my understanding grew, moving from the concrete to the abstract, just as Mr. John Locke suggests. I went from “meat,” to “food,” to “good,” and hence to “a good,” and soon I was able to read whatever I could lay my paws upon. Lounging on the sofa, I devoured novels. Crouched at the desk, I chewed over philosophical volumes. Finding myself standing over scattered pages, I could not help but read what lay beneath my pug’s toes.

I scanned several pages quickly, and then returned to the top sheet to read with more care. Bafflement on a pug’s face is not easy to recognize due to the wrinkling of an already-puckered brow, but I believe my expression must have been expressive of the confusion that overcame me then. Spewed across the floor of my Master’s parlour lay such a variety of documents, I did not know what to think of this strange gift, my portmanteau.

Some of the pages were printed, while others were manuscripts in various hands. I nosed past a frontispiece, and pawed through letters. I found a magistrate’s notes, a sinner’s confession, and a last will and testament. I counted a number of my Master Hogarth’s own prints, including the one on which I had slept, which was his last completed work. But even on this familiar ground, I felt muddled, for the pictures in this portmanteau were all scenes stolen from various tales and did not belong to a single modern moral subject.

I scratched my head with my rearmost leg. The reason for this collection, I could

not guess. I had snatched my relic from beneath my Master’s very bed, but I hardly knew why.

By that time, my thinking had begun to be troubled by those same urges that so disturbed Gulliver when restrained by the Lilliputians. But Gulliver was large where I was small, and when I turned to the door, I found that someone in the night had shut it tight. Now, the doorknob hung as golden and unattainable as the sun. I pointed my snout and howled for all I was worth, and just as I began to fear the portmanteau papers might serve only to protect the parlour rug, the serving girl heard me and, with a cry of pity, opened the door.

Out in the street, I made water next to a horse’s hoof, just as now I might piss on a car’s tire. But wherever the century, the sensation never alters—it is always blessed relief.

Now Mary Lewis herself came down and shook her head at what she termed my pitiable cries and lamentations. But she fed me and then took me upstairs again to my Master’s bedchamber, where someone had thrown open the window. Death’s brown fug, once so unbearable to my dog’s nose, retreated to the edges of the room, a faint and diminished horror. Now the enormity of my loss threatened to burst apart my heart. The sight of the shrouded, still figure on the bed silenced me, and I curled myself into a fold of the bed-curtains and set my head on my paws. There I was allowed to remain, undisturbed, and how grateful I was that my Master’s family took my bereavement no less seriously for all it flowed from a mere pug dog.

The following day, Jane Hogarth herself came up to London, arriving grim and determined but leaning on Mary Lewis even before the girl could shut the hall door behind her. When the gloomy conclusion of my Master’s affairs at last allowed us time to return to Chiswick, the leather portmanteau came also. I myself dragged it into the pile to be loaded on the back of the carriage. Sorrowing, distracted servants made my deception simple, and I had the satisfaction of observing my case roped to the rest and lashed above hooped wheels. Then I followed Jane into the body of the carriage, both of us climbing into the worn seats—no coach dog I. Jane gave the command, and our London life sank away with the jerk and jangle of the harnessed bays. We clattered westward, the wind rising, and the leaves flapping yellow and black as we passed.

Pugg's Portmanteau

Pugg's Portmanteau